January or Penamujuiku’s in Mi’kma’ki

By: Bryan Martin

Walking to the ice-covered sea with kids and dog in tow in January. Photo: B. Martin

Oh January! Also known as Penamujuiku’s in Mi’kma’ki, the Traditional Ancestral Territory on which I call home, now known as the Maritimes. Penamujuiku’s means the month that the punamu come into the estuaries near shore to spawn under the sea ice. Punamu are more commonly known as tomicod, frost fish, or Atlantic Tomcod, and have always been an important winter food for the Mi’kmaq. They can be observed directly from the waters edge through cracks or holes in the sea ice at high tide. These little fish look similar to shrunken down versions of their gadus cousins, the infamous Atlantic codfish. One of the unique features of the punamu is their ability to produce antifreeze proteins that allow them to tolerate below-freezing water temperatures. They are also delicious (for those that are into that sort of thing!).

The only reason I have come to know so much about this marvelous little fish is my interest in the sea, no matter the season. In January I admire the punamu, observing them through the cracks in the ice as I wander the shoreline. It is a reminder that the ocean is alive 12 months of the year, in all weather conditions.

The Sea Is For All Seasons

Alternate names: Tomcod, frostfish

Scientific name: Microgadus tomcod

Common name in English: Tomcod

Common name in Mi’kmaq: Punamu

There was a time when I would say goodbye to the sea in September or October, only observing her cold wintery beauty from afar until May or June. It wasn’t until a few years ago, with some gentle coaxing from friends, that I began to extend my swimming, or perhaps more precisely, “dipping” season. It was a way for me to not only continue interacting with the ocean over the winter, but also a way to continue having the ocean front of mind. By venturing down to the water’s edge in all seasons and temperatures, I can see that the ocean continues to teem with life and I can observe all the different processes that are happening around and under the ice. The sounds that the slush makes as it slowly attenuates the waves along the shore is calming, those first crackles as the ice begins to freeze is mesmerizing. Once the thicker ice has formed, the harbour water underneath the ice becomes calm and clear in the absence of waves. A normally turbid water seems crystal in comparison. Creatures that are ‘cold blooded’, or exothermic, move more slowly, and seaweeds sway as if in no particular hurry. With the exception of our frosty punamu, life under the ice slows down. Even the harbour seals popping up through breathing holes seem a little more laidback this time of year. Their natural predators have long left for warmer waters and the silence on the ice allow them to hear us from far away.

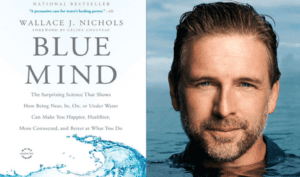

Dr. Wallace J. Nichols is a scientist, activist, community organizer, author of many books including, “Blue Mind,” and a dad. He helps people reestablish healthier, more creative and regenerative relationships with themselves, each other and their environment through water, wonder, wellness and wildlife.

The critters under the ice are not the only ones to slow down this time of year. January tends to be a time when people also slow down after the holiday season. The shorter days and cold weather can have us holed up inside for days at a time. Some people cope well with this slow time of year by catching up on indoor projects, reading that new book, or learning how to bake bread, while others may feel a little SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) or ‘blue’. That’s where nature can help, specifically the ocean.

Wallace J. Nichols describes in his book: Blue Mind – The surprising Science that Shows How Being Near, In, On, or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected, and Better at What You Do, that being near water can diminish anxiety, reduce stress, increase creativity, bring us peace, and improve our overall well being. It can remind us how our happiness is tied to the natural world, and why it’s important to keep the natural world healthy and thriving. Why only experience those beneficial effects during the summer?

Connect to Nature

Waves and sea ice crashing on shore in Newfoundland, Canada

If you are feeling extra brave walking along a winter shoreline, cold water swimming, or dipping, can also connect you to nature. I have been dipping for around five years now, and am hooked. I like to get into the cold salt water as it seems to reset my mind by way of it taking all of my concentration and forcing me to be in the moment where nothing is more important. I tend to feel a being part of nature with a much deeper appreciation for the sea after a cold dip. If you live in a tidal area, catching the tide when it is just right may force you to be out before the crack of dawn under a moonlit sky. Or perhaps you will get out late in the day when the sun is shining her last pink rays over the ice as you slip into the cold water. But you do not have to get wet to reap the benefits of the ocean, you simply need to be present and by her side and witness her in all colours and seasons. Whether dipping or not, getting out to the seashore can be a great way to find peace and calm during a time of year the shoreline is probably its quietest. Maybe if you get really close to the ice, you might see the punamu, moving about, enjoying the cold ocean.

Safety First

*As a disclaimer, never venture out on to ice unless you have an intimate knowledge and experience with the local tides, currents, depths, and ice thickness, and never get into water through ice that is deeper than your waist (squat down instead) as it may be difficult to get back out. Similarly, never walk on the ice where the water is deeper than your waist. Check with your doctor before cold water dipping and always swim with a buddy.

About the Author

Bryan Martin, Photo: L. Campbell

Bryan Martin grew up near the Baie des Chaleur in northern New Brunswick and, despite living, studying, or working in all four Atlantic Provinces, has never strayed far from the ocean. Being an outright ocean fanatic, you will often find him swimming, paddling, or advocating for the ocean. Bryan loves to connect with people about the sea, currently works as the Ocean Advisor with the Maritime Aboriginal Peoples Council, and sits on the CaNOE board of directors. He currently lives within a stone’s throw from the harbour in Epekwitk/PEI with his wife, two young girls, and ‘little’ black lab.

Leave a Comment

Never Miss Out

Sign up to receive notifications whenever we post a new article and stay updated on all things ocean!

[email-subscribers-form id=”1″]